Verizon's 'perma-cookie': Just another example of how ISPs invade, threaten our privacy

**Update: Verizon forced 'supercookies' on all of their customers until March 2015, when several senators raised privacy concerns over the practice. One year later, in March 2016, Verizon agreed to a three-year consent decree and was forced to pay a $1.35 million fine after the Federal Communications Commission found the company violated the privacy of its users.**

For two years, Verizon Wireless, has been secretly altering people's traffic by injecting a Unique Identifier Header, or UIDH, into all HTTP (web) requests. This UIDH allows advertisers to see Verizon customers' identities as they browse unencrypted websites.

The story, which was reported in Wired and Ad Age, has security experts up in arms.

How the UIDH permacookie works

The UIDH is a unique combination of letters, numbers, and characters that identifies each Verizon Wireless customer. Let's say you're using your computer, smartphone, or any other device on an ISP that tracks you. As you browse the web, your device sends requests over the network to different servers on the web. Your ISP then inserts the UIDH, a unique tracking code, into each of your requests.

Since you're the ISP's customer, and since they run the network infrastructure, they know exactly which person made which network request, so they can match your tracking code to you. Not only does this give your ISP a lot of information about what sites you're looking at, but it also makes it possible for other websites to track what you do online, too. Yikes.

For more, you can check out the infographic by Jonathan Mayer, a computer scientist and lawyer at Stanford who cobbled together the diagram based on information gleaned from Verizon's patents and marketing materials.

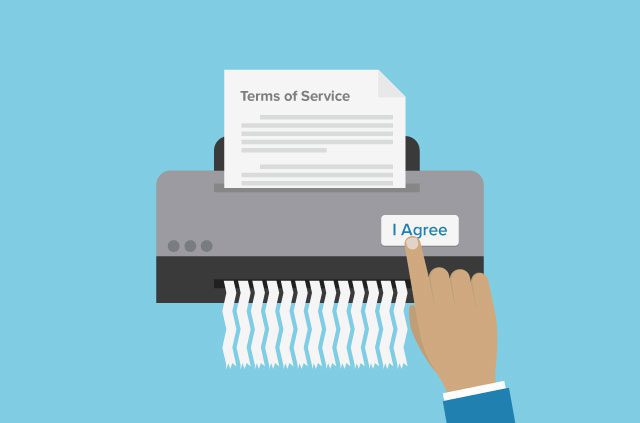

As Mayer points out, "Whatever the merits of Verizon’s new business model, the technical design has two substantial shortcomings. First, the X-UIDH header functions as a temporary supercookie. Any website can easily track a user, regardless of cookie blocking and other privacy protections. No relationship with Verizon is required."

Secondly, "while Verizon offers privacy settings, they don’t prevent sending the X-UIDH header. All they do, seemingly, is prevent Verizon from selling information about a user." Yikes.

This was confirmed by Verizon spokesperson Debra Lewis, who told Wired that there's no way for users to turn off UIDHs - but that they could opt out of Verizon's Relevant Mobile Advertising program

As Electronic Frontier Foundation technologist Jacob Hoffman-Andrews told Wired, "ISPs are trusted connectors of users and they shouldn't be modifying our traffic on its way to the Internet."

With confirmation that Verizon is uniquely identifying and tracking its users, who knows what other ISPs are doing?

My ISP is interfering with my Internet traffic... what do I do?

Here are some things that don't work, as tested and reported by Cody Dunne, a Research Scientist at the IBM Watson team:

- private browsing sessions

- "do-not-track" features

Dunne found that neither private browsing nor do-not-track prevented UIDH interference.

So, how to prevent the UIDH tracking?

Always use HTTPS by using something like HTTPS Everywhere. However, this isn't realistic as many websites don't support HTTPS.

How about switching to other ISPs (Internet Service Providers)? While some people have floated the idea of switching wireless providers all together, the truth is that there's no guarantee that your ISP isn't tracking you or spying on you. Therefore, switching to a different ISP might actually mean giving a different ISP the opportunity to track you.

Bottom line: using a VPN is the best way to prevent your ISP from gathering or sharing data about you.

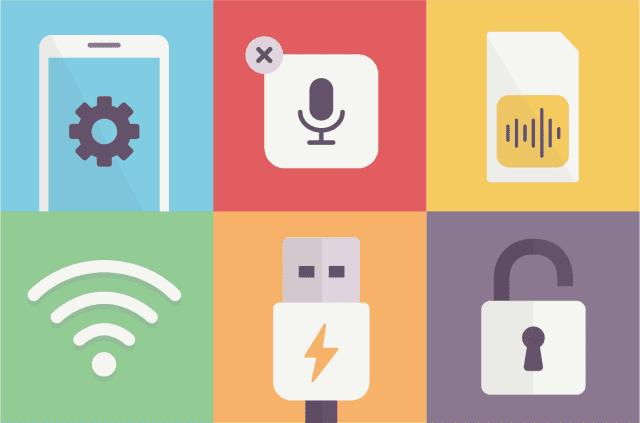

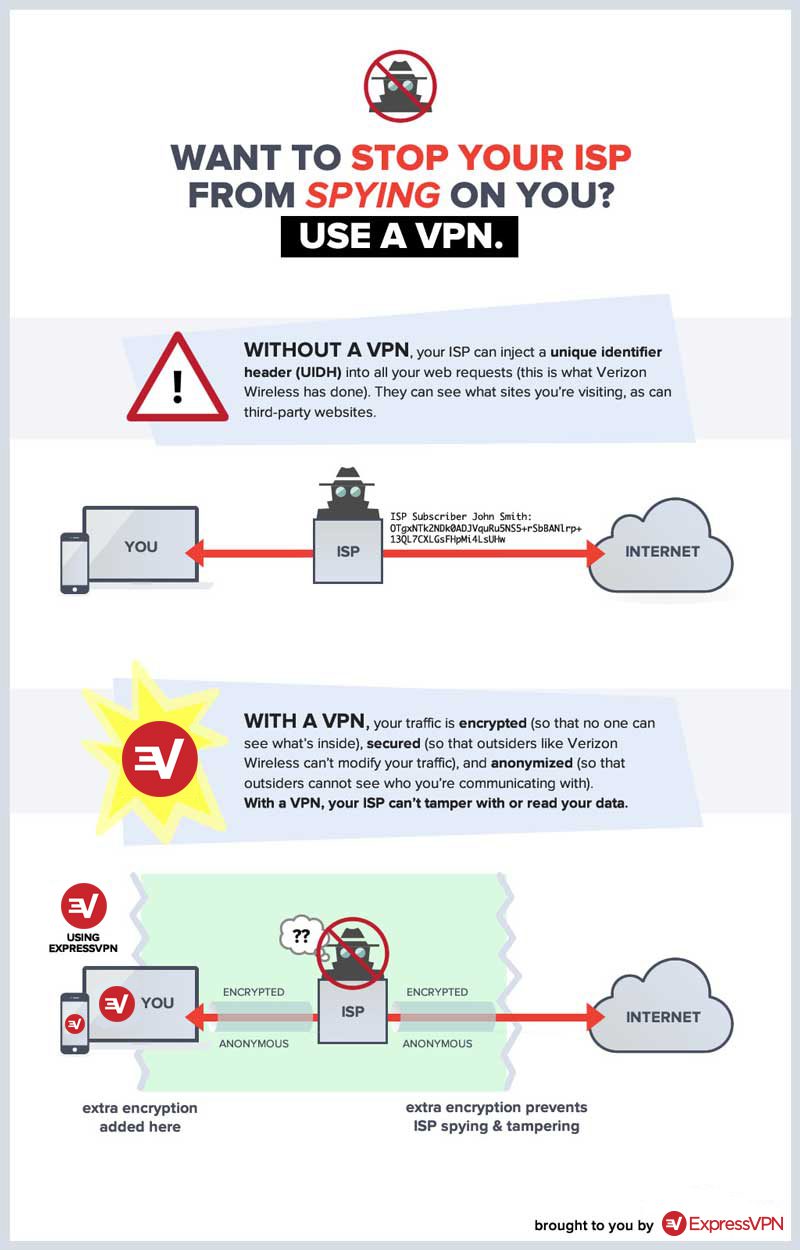

A VPN stops your ISP from tracking, spying on, or interfering with your Internet use by:

- encrypting your traffic, so that outsiders cannot see what's inside;

- securing your traffic, so outsiders can't modify your traffic. and

- anonymizing your traffic, so that outsiders cannot see who you're communicating with (check out our post about metadata for more).

Check out our infographic below for a visualization about how it works.

If you're not already using a VPN, then the idea that your ISP could potentially be spying on you (or allowing others to spy on you) should give you ample reason to use one today.

ExpressVPN offers easy-to-use VPN apps for Windows, Mac, Android, iOS, Routers, and Linux. If you believe in your right to privacy, then you need a VPN.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN